Research Article - (2024) Volume 15, Issue 5

Abstract

Background: Fatigue remains one of the most common and disabling problems in Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and several factors could contribute to the development and/or exacerbation of this symptom. So, the aim of this study is to assess fatigue in MS patients and identify its correlations with other clinical, functional and radiological signs.

Materials and methods: This is a prospective collection study that included adult patients with MS. In addition to clinical and radiological assessment, we used the Visual Analog Scale-fatigue (VAS-f) and Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) self-questionnaire to assess fatigue and the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) for disability. Univariate and multivariate analysis was performed using Social Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 software.

Results: The mean age of the 103 patients (71 women and 32 men) was 41.57 ± 11.22 years and the mean EDSS was 5.12 ± 1.97. Fatigue was found in 94 patients among whom 26% had severe fatigue (VAS-f ≥ 7). We found that 53.2% had moderate fatigue and 15.6% had severe fatigue according to the FSS. We did not find an association between fatigue severity and EDSS, age, sex and place of birth/residence; however, fatigue severity was correlated with the duration of disease progression, progressive form of the disease, depressed mood and presence of demyelinating plaques in the cerebellum.

Conclusion: The appropriate management of fatigue in MS requires first a good evaluation and a good semiological analysis.

icsatc neodeme advancedstructurescorp floormachinebrush scpe jcamasonry sages-tunisie sbsteel technomailleplus bolkan vaalea nsblueprinting mycleanairdoctors nycgeneralproroofing gabgadgets prsnekkern uniquescaffoldingsystems villaguicciardini acerpackaging acjstucco prontointervento-multiservice printersupplygiant sarel takkatiimi dragonshollow mazelsupply alfalchetto reliablegeneralagency lckenterprises realizzazione-giardini dmcindustries shop chathambrass ilfaroservizi soilmechanicsdrilling colorfullyyours agcsound carriere carnavaldetournai falconauto codingxcamp davinci-trondheim thebestofcolumbia cooperativetissage outsourcedmarketingpros tlc dawnnhough doubleclick pdirealty hattrennet az-bizsolutions jamaistropdart frontdata unitycreations fortisarezzo bspo-ken codar-confection theboulders bakerpersonnel fantasyphotographyandvideo fuleky tanssikoulutria ladybi swimanddance scuolavelatoscana x-pack creativeglazing lucagnizio sigaretteelettronichepisa mayiindustries frigo-clim elgars leoemma hotelalcantara el-pro therefore thebestofjacksonville nykran masmoudi thebestofspokane cogepre detrecruitment laresidencelepartage chimneycompanyboston awarepedia res-botanica recipefy semap thebestofcincinnati bb-one fourtech thebestofjoliet ajproduce jerryshulmanproduceshipper lckcabinetryny drivingtechniquesmadeeasy accademiaestetica pizzamaison schoonheidssalonbianca cabinsbrevardnc mrbrushes atlasrolloff hatip-medikal vezcocorporation thebestofcoloradosprings filtaclean monteleeper flyfisher ellatafa associazionepugliesiapisa unitycreationsltd maketeamstudiot douglasclear packagingpro softm allstarbeerinc burtonsupply footballscouting profondacreation johnvravickddsms fireislandbuilder advancedcontrolsolutions chittorgarhtaxiservices live-now orologeriatoscana racinemode thebestofwilmington agro-services violiner sandinghouse the-complete-package thebestofrichmond rcollision meubleskarray mes-recettes lawsandtaxes tavgrupp mkproducts royscottmarine taxi contreras-stockman sigmaweb de-noord thebestofkansascity maisonmedicaledelaeken recycledrubberpavers surfacingsystems unitedfidelityinc enokplan hunterremodeling edmersupply amerequipint sanilabcorp igglesis christiannursingregistry united-royal cantodelfiume northsidedeliny menuiserie-delbart passeritartufi justmyvoice ablefiresprinklers accantoalcentro ckperformance khalfallahpneus anti-flood-barriers bmstyle autosangiorgio-mercedes-benz carmagnino viipurinurheilijat multipack cma-eng mcafeerealty adrianaperciballi loconteedilecostruzioni konarprecision unityrubberco unityrubberproducts dante tela marathongranite baltimahalworcester heimdalbygg alstateprocessservice italydreamtour wemcocastingllc yachtbritesigns ecoledecroly-renaix anchorseniorapartments royalburton sk-veilag giannacapoti hubiteg customcommercialconstruction edm-nivelles probat-tunisie bachlawyer robertex inbora gpbconstruction tekstschrijver-tim bdsit trepro himalayanlounge lazersharpplumbing nycollisionking marinanova gealcorp nygabe maritimecoverage justmyvoice jukumech quimicolsa hayat-med aldrovandiauto michaelbenaltinc korenas sandvet americanmufflerautorepair justmyvoice liacoustics dminteriors agenziapromotech ligbtour internormfirenze justmyvoice zouila kohalmiferenc ashgroveresort ilmacinapepe suzukibandit hihna islandfishli prontointerventofabbro24h thebestofmidland thebestofportland dsgnaturaeambiente rimpex-medical giadaguidi royalroseappliances normas monicavignoliniluxury reddalsand defigners projektorilamput qtbservices labandas totalconceptdesign elannonnayttamo begmaterialiedili bardsdans samuelmanndds marksmenmfg demo17 chinafinewines coralia ivar-moe tournailesbains consew luisaprofumeriashop chimneycompanywestchester danapoly 268dental uspaerospace melonerp matcoservice emperorsoft cantare fninc greenpowerchemical westendsupply domobios unitysurfacingsystems martemoen hamptonssepticservices housatonicpaper sj-transport epsl-tunisie sungoldabrasives collinscreative barbarottomachinery soep thebestofalexandria straightlineconst itcimpianti hattrem-trafikkskole federalnetworks ppattorneys ceteau fbperformance coltgateway coolservice4u garaconfection bellformalwear abcconcretepumping mysantaria accurateindustrialmachining schmugerhardware thebestofjackson bellwetherstaffing sweetkarmadesserts tonerhuset mongilschool polycliniquelaouani buonidentro schoolbusmirrorsonline qlstransportation andereuropa cleanpressiondrycleaner bsyd planetlimony thebestoflasvegas csgmfoodequip potensial potiez invitiing tomscorvetteshop thebestbaltimorebusinesses honefoss thebestofoakland hydeparkdenim scmanndds sirreal totalpreferredsupply futureshockcorp myrtun

Keywords

Sclerosis, Fatigue, Radiological assessment, Expanded disability status scale, Visual analog scale

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory and neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system, characterized by numerous symptoms during its evolution. Fatigue remains one of the most frequent and debilitating problems of MS patients. As its clinical presentation is highly variable, it seems likely that the same applies to its pathophysiology. Several factors could contribute to the development and/or exacerbation of fatigue in MS this requires a fairly comprehensive assessment in order to properly manage MS patients.

Objective of the study was to assess fatigue in patients with MS and to identify its correlations with other clinical, functional and radiological signs.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This is a descriptive, bi-centric study of prospective collection, relating to patients with MS, carried out at the level of the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Departments of the Center Hospitalo-Universitaire of Oran (CHUO) and the Hospital Military Regional University of Oran (HMRUO).

Study population

All the patients with MS referred to our level for rehabilitation care.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with definite MS; patients who were diagnosed according to the McDonald 2005/2010 criteria; patients who were aged 18 years and over, and whichever clinical form and stage of disease were included in this study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who denoted a flare-up of the disease in the last 6 months; patients with cognitive state incompatible with understanding the instructions; patients with the presence of serious psychiatric pathology with unstabilized or untreated inflammatory, infectious or cardiac disorder and patients having surgical history recently (less than six months) were excluded from the study.

Duration of the study

The complete duration of the study is 2 years and 6 months (from January 2017 to June 2019). Univariate and multivariate analysis was performed using SPSS 20 software. For the main analysis of the evolution of MS, the residual disability levels of the EDSS scale (Expanded Disability Status Scale) at the last consultation were used. We used the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) fatigue and the self-questionnaire Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) French version to assess the severity of fatigue.

Results

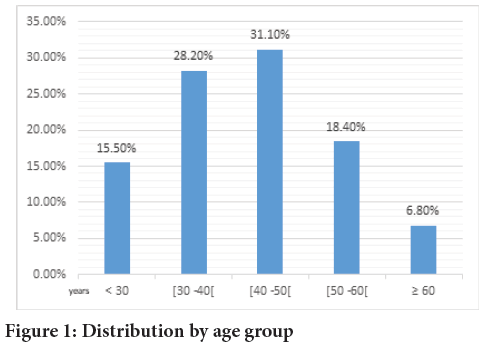

Age

The mean age of patients in our study was 41.57 ± 11.22 years with minimum age of 19 years and maximum age of 69 years while 56.3% of patients were over 40 years of age (Figure 1). Whereas the mean age of patients in our study at diagnosis was 35.23 ± 11.41 years, with minimum age of 10 years (1 patient) and maximum age of 69 years (1 patient) and the mean age of onset of symptoms was found to be 31.83 ± 11.52 years which ranged from 10-65 years.

Figure 1: Distribution by age group

Gender

Analysis of the results shows predominance of females. Among 103 patients, 71 were women (68.9%), while men accounted for 31.1% (32 patients). Female/Male (F/M) gender ratio was 2.21. According to EDSS, the mean EDSS scale was 5.12 ± 1.97, with a minimum of 1 and maximum of 9 patients respectively. EDSS evaluation enabled us to classify our patients according to their current disability situation into 4 levels (Table 1). 28 patients (27.2%) had minimal disability with no locomotion limitations; 21 patients (20.4%) had moderate disability with progressive reduction in walking perimeter, while 35 (34.0%) had significant disability who relied on technical aids for ambulation and 19 patients (18.4%) had lost the complete ability to walk outdoors and were variably confined to a wheelchair.

| Severity of disability | EDSS | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal disability | <4 | 28 | 27.2 |

| Moderate disability | 4-6 | 21 | 20.4 |

| Significant disability | 6-7 | 35 | 34 |

| Severe disability | ≥ 7 | 19 | 18.4 |

| Total | 103 | 100 | |

Table 1: Distribution by severity of EDSS disability

Assessment of fatigue

We were able to assess fatigue in 100 patients among our population by the VAS fatigue and only 77 patients by the FSS because of language problems (some of our patients do not speak French). Fatigue was found in 94 (91.2%) patients; it was of variable intensity and severity from one subject to another and reported at any time of the day (Figure 2).

Figure 2: FSS by disability class EDSS

Note: ( ): Male and (

): Male and ( ): Female

): Female

According to VAS fatigue, the mean VAS-fatigue scale of the 100 patients assessed was 4.93 ± 2.066 (minimum: 0 and maximum: 8) and 26% of patients had severe fatigue (VAS ≥ 7) (Table 2).

| Eva fatigue | Number | Percentage (%) | % Validated |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6 | 5.8 | 6 |

| (1-4) | 16 | 15.5 | 16 |

| (4-7) | 52 | 50.5 | 52 |

| ≥ 7 | 26 | 25.2 | 26 |

| Total | 100 | 97.1 | 100 |

Note: 0: No fatiguel; 1-3: Low fatigue ; 4-6: Moderate fatigue and ≥ 7: Intense fatigue

Table 2: Eva fatigue distribution

According to the FSS, the mean FSS of the 77 patients evaluated in our series was 4.17 ± 1.53 (minimum: 0 and maximum: 7). We found that 53.2% had moderate fatigue and 15.6% had severe fatigue (Table 3).

| FSS value | Interpretation | Number | percentage% | % Validated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1-4) | Probable fatigue | 24 | 23.3 | 31.2 |

| (4-5.5) | Moderate fatigue | 41 | 39.8 | 53.2 |

| ≥ 5.5 | Severe fatigue | 12 | 11.7 | 15.6 |

| Total | 77 | 74.8 | 100 |

Table 3: Distribution according to the severity of fatigue assessed by the FSS

Fatigue and age

Statistical analysis showed no significant relationship between age of MS onset and/or patients’ current age and fatigue severity (p=0.302 (VAS) and p=0.98 (FSS)) (Tables 4 and 5).

| Eva fatigue by class | Age of onset (years) | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | (30-40) | (40-50) | (50-60) | ≥ 60 | ||

| Absent | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Minimal fatigue | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 16 |

| Moderate fatigue | 4 | 17 | 20 | 9 | 2 | 52 |

| Severe tiredness | 3 | 12 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 26 |

| Total | 10 | 36 | 30 | 17 | 7 | 100 |

Table 4: Distribution of fatigue severity according to age of onset

| Charactersistics | Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal fatigue (1-4) | Moderate fatigue (4-5.5) | Intense fatigue (≥ 5.5) | Total | |||

| Gender, n (%) | Women | 14 (26.41) | 29 (54.71) | 10 (18.86) | 53 (100) | p=0.12 |

| Men | 10 (41.66) | 12 (50) | 2 (8.33) | 24 (100) | ||

| Current age (in years), n (%) |

<30 | 3 (25) | 6 (50) | 3 (25) | 12 (100) | p=0.98 |

| (30-40) | 8 (33.33) | 15 (62.5) | 1 (0.04) | 24 (100) | ||

| (40-50) | 7 (28) | 15 (60) | 3 (12) | 25 (100) | ||

| (50-60) | 2 (18.18) | 5 (45.45) | 4 (36.36) | 11 (100) | ||

| ≥ 60 | 4 (80) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 5 (100) | ||

| Duration of MS progression (years), n (%) |

<10 | 18 (35.29) | 27 (52.94) | 6 (11.76) | 51 (100) | p=0.04 |

| (10-20) | 5 (31.25) | 8 (50) | 3 (18.75) | 16 (100) | ||

| ≥ 20 | 0 (0) | 6 (66.66) | 3 (33.33) | 9 (100) | ||

| Residential zone, n (%) | Coast | 19 (29.68) | 36 (56.25) | 9 (14.08) | 64 (100) | p=0.91 |

| High-plateau | 4 (40) | 3 (30) | 3 (30) | 10 (100) | ||

| Sahara | 1 (33.33) | 2 (66.66) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | ||

| EDSS by class, n (%) | Minimally handicap | 9 (42.85) | 11 (52.38) | 1 (4.7) | 21 (100) | p=0.39 |

| Moderately handicap | 3 (18.75) | 10 (62.5) | 3 (18.75) | 16 (100) | ||

| Important handicap | 8 (27.58) | 14 (48.27) | 7 (24.13) | 29 (100) | ||

| Severely handicap | 4 (36.36) | 6 (54.54) | 1 (9.09) | 11 (100) | ||

| Form of MS, n (%) | RR | 15 (35.71) | 25 (59.52) | 2 (4.76) | 42 (100) | p=0.024 |

| SP | 6 (26.08) | 12 (52.17) | 5 (21.73) | 23 (100) | ||

| PP | 3 (27.27) | 4 (36.36) | 4 (36.36) | 11 (100) | ||

| Benign | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | ||

| Pain, n (%) | Absent | 10 (47.61) | 11 (52.38) | 0 (0) | 21 (100) | p=0.061 |

| Neuropathic | 7 (23.33) | 16 (53.33) | 7 (23.33) | 30 (100) | ||

| Nociceptive | 4 (26.66) | 9 (60) | 2 (13.33) | 15 (100) | ||

| Iatrogenic | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | ||

| mixed | 3 (37.25) | 2 (25) | 3 (37.25) | 8 (100) | ||

| Depressive mood, n (%) | Absent | 6 (27.27) | 12 (54.54) | 4 (18.18) | 22 (100) | p=0.14 |

| Present | 15 (32.60) | 24 (52.17) | 7 (15.21) | 46 (100) | ||

| Cerebellum demyelinisation, n (%) | Absent | 14 (50) | 11 (39.28) | 3 (10.71) | 28 (100) | p=0.008 |

| Present | 7 (17.07) | 26 (63.41) | 8 (19.51) | 41 (100) | ||

| Brain stem demyelinisation, n (%) | Absent | 13 (35.13) | 16 (43.24) | 8 (21.62) | 37 (100) | p=0.82 |

| Present | 9 (29.03) | 19 (61.29) | 3 (9.67) | 31 (100) | ||

| Spinal cord demyelinisaion, n (%) | Absent | 6 (27.27) | 12 (54.54) | 4 (18.18) | 22 (100) | p=0.63 |

| Present | 15 (32.6) | 24 (52.17) | 7 (15.21) | 46 (100) | ||

Table 5: Correlation between fatigue severity and selected demographic, clinical and radiological data

Fatigue and duration of progression

We noted that there was a significant relationship between fatigue severity and duration of disease progression (p=0.021), so 88.2% of the 34 patients who were diagnosed 10 years ago or more had moderate to severe fatigue (Table 5).

Fatigue and gender

We found no correlation between fatigue severity and gender (VAS p=0.44, FSS p=0.11), but female MS patients in our series suffered more fatigue than males. We found that the F/M gender ratio for patients with “probable fatigue” according to FSS was 1.4, whereas it was 5 for those with “severe fatigue” (Table 5).

Fatigue and area of residence

Overall, statistical analysis did not find a correlation between fatigue severity and place of birth and/or residence (p=0.06), but it should be noted that over 81% of patients who had lived in the littoral region had moderate to severe fatigue, compared with 65% in the highlands and only 40% in the south (Table 5).

Fatigue and form of MS

Statistical analysis revealed a significant correlation between the severity of fatigue and the progressive form of MS (p=0.02). Fatigue was lower in MS patients with Relapsing-Remitting (RR) MS than in those with progressive MS (Primary Progressive (PP), Secondary Progressive (SP)).

Fatigue and pain

Statistical analysis showed no significant relationship between pain and fatigue severity (p=0.153), but it was noted that 58.33% of patients with severe fatigue had neuropathic pain. (Table 5).

Fatigue and depressed mood

Depression was diagnosed using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of mental disorders criteria. We found that depression was present in 45 patients (43.7%). Depression was not correlated with fatigue severity (p=0.073), but we did note that 9 out of 10 patients with severe fatigue had a depressed mood.

Fatigue and location of demyelinating plaques

We found a significant relationship between the presence of cerebellar lesions and the severity of disability (p=0.008) (Table 5).

Discussion

There is no universally accepted definition for fatigue in MS. The Multiple Sclerosis Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Paralyzed Veterans of America have adopted the following definition-fatigue is a subjective lack of physical and/or mental energy that is perceived by the individual or caregiver as interfering with usual and desirable activities (Multiple sclerosis Council, 1998)

Unlike fatigue experienced in a healthy population, fatigue in MS is different. It is chronic, permanent, both physical and mental, and could prevent prolonged physical functioning, be aggravated by heat which is responsible for significant impairment of quality of life (Béthoux F, 2006; Krupp LB, et al., 1988).

Self-report scales are considered one of the best methods of gathering information on fatigue, as it is the respondent’s own report of his or her experiences.

Fatigue in MS can have a variety of origins, but has been assessed in its entirety, partly due to the lack of locally translated rating scales.

Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) and Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) are longer questionnaires, used less frequently in the MS literature (Andreasen AK,et al., 2011). Thus, FSS developed for use in MS (Krupp LB, et al., 1989; Drenska K, 2018) was used in our study.

Long underestimated and neglected, fatigue is nevertheless extremely frequent in MS, according to studies; it occurs in 80%-97% of cases, mainly in primary and secondary progressive forms (Moreau T and Du Pasquier R, 2017; Hameau S, et al., 2017) and our results are similar to those in the literature. Fatigue was reported in 94 patients (91.2%), varying in intensity and severity from one subject to another, with 26% of patients presenting with intense fatigue (VAS ≥ 7).

Fatigue is a predictive factor of work disability independently of other neurological deficits (Béthoux F, 2006), and several studies have shown that motor disability is not related to fatigue level (Garg H, et al., 2016; Lerdal A, et al., 2003).

Our results concur with those of the literature, and there was no significant correlation between fatigue intensity and disability severity (VAS; p=0.159 and FSS; p=0.332).

However, we found that patients with MS for more than 10 years suffered more fatigue, irrespective of their disability severity as assessed by the EDSS.

The study confirmed the absence of a link between fatigue and gender, confirming the findings of previous research which also showed no association of any kind (Trojan DA, et al., 2007; Patrick E, et al., 2009). However, our study showed that the prevalence of severe fatigue was higher in women.

We did not find any relationship between pain and fatigue, which for some authors was consistently correlated at baseline and follow-up with pain intensity, but the presence of neuropathic pain was associated with severe fatigue.

Our study did not reveal a significant correlation between FSS scores and the presence of depressed mood, which is in line with the opinion of Stroud NM and Minahan CL, 2009, whereas the relationship between depression and fatigue in MS patients reported in previous studies was established (Feinstein A, 2011). Radiologically, we found a significant correlation only with the presence of demyelinating lesions in the cerebellum (p=0.008), something that is under-researched in the literature, and other volumetric parameters are interpreted such as the different volumes of the constituted grey nuclei and cortical thickness (Dhia RB, et al., 2022; Patejdl R, et al., 2016).

Conclusion

Fatigue is a frequent symptom in multiple sclerosis, aggravating patients’ disability. According to the results of our study, fatigue may be aggravated and become troublesome when it occurs in patients with duration of disorders exceeding 10 years, or who present a progressive form of the disease, or demyelinating plaques in the cerebellum. Patients who are female, live on the coast (humidity) or have a depressive mood may suffer more severe fatigue than others. Appropriate management of fatigue in MS requires a good evaluation and semiological analysis.

References

- Multiple sclerosis Council for clinical practice guidelines. Fatigue and multiple sclerosis: Evidence-based management strategies for fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Clinical practice guidelines. The Council. 1998.

- Béthoux F. Fatigue et sclérose en plaques. InAnnales de réadaptation et de médecine physique. Elsevier. 2006; 49(6): 265-271.

- Krupp LB, Alvarez LA, LaRocca NG, Scheinberg LC. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1988; 45(4): 435-437.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Andreasen AK, Stenager E, Dalgas U. The effect of exercise therapy on fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2011; 17(9): 1041-1054.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale: Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989; 46(10): 1121-1123.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Drenska K. Non-motor symptoms in multiple sclerosis. 2018.

- Moreau T, Du Pasquier R. La sclérose en plaques. John Libbey Eurotext. 2017.

- Hameau S, Zory R, Latrille C, Roche N, Bensmail D. Relationship between neuromuscular and perceived fatigue and locomotor performance in patients with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017; 53(6): 833-840.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Garg H, Bush S, Gappmaier E. Associations between fatigue and disability, functional mobility, depression, and quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2016; 18(2): 71-77.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Lerdal A, Celius EG, Moum TJ. Fatigue and its association with sociodemographic variables among multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2003; 9(5): 509-514.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Trojan DA, Arnold D, Collet JP, Shapiro S, Bar-Or A, Robinson A, et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Association with disease-related, behavioural and psychosocial factors. Mult Scler. 2007; 13(8): 985-995.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Patrick E, Christodoulou C, Krupp LB, New York State MS consortium. Longitudinal correlates of fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2009; 15(2): 258-261.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Stroud NM, Minahan CL. The impact of regular physical activity on fatigue, depression and quality of life in persons with multiple sclerosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009; 7: 1-10.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Feinstein A. Multiple sclerosis and depression. Mult Scler. 2011; 17(11): 1276-1281.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Dhia RB, Mouna A, Mhiri M, Asma A, Gouta N, Frih-Ayed M. Fatigue et sclérose en plaques: Corrélations clinicoradiologiques. Revue Neurol. 2022; 178: S120.

- Patejdl R, Penner IK, Noack TK, Zettl UK. Multiple sclerosis and fatigue: A review on the contribution of inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration. Autoimmun Rev. 2016; 15(3): 210-220.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

Author Info

Kehli M*, Kobci Y, Mammeri DM and Layadi KCitation: Kehli M : Fatigue during Multiple Sclerosis

Received: 08-May-2024 Accepted: 24-May-2024 Published: 31-May-2024, DOI: 10.31858/0975-8453.15.5.166-170

Copyright: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ARTICLE TOOLS

- Dental Development between Assisted Reproductive Therapy (Art) and Natural Conceived Children: A Comparative Pilot Study Norzaiti Mohd Kenali, Naimah Hasanah Mohd Fathil, Norbasyirah Bohari, Ahmad Faisal Ismail, Roszaman Ramli SRP. 2020; 11(1): 01-06 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2020.1.01

- Psychometric properties of the World Health Organization Quality of life instrument, short form: Validity in the Vietnamese healthcare context Trung Quang Vo*, Bao Tran Thuy Tran, Ngan Thuy Nguyen, Tram ThiHuyen Nguyen, Thuy Phan Chung Tran SRP. 2020; 11(1): 14-22 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1.3

- A Review of Pharmacoeconomics: the key to “Healthcare for All” Hasamnis AA, Patil SS, Shaik Imam, Narendiran K SRP. 2019; 10(1): s40-s42 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1s.21

- Deuterium Depleted Water as an Adjuvant in Treatment of Cancer Anton Syroeshkin, Olga Levitskaya, Elena Uspenskaya, Tatiana Pleteneva, Daria Romaykina, Daria Ermakova SRP. 2019; 10(1): 112-117 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1.19

- Dental Development between Assisted Reproductive Therapy (Art) and Natural Conceived Children: A Comparative Pilot Study Norzaiti Mohd Kenali, Naimah Hasanah Mohd Fathil, Norbasyirah Bohari, Ahmad Faisal Ismail, Roszaman Ramli SRP. 2020; 11(1): 01-06 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2020.1.01

- Manilkara zapota (L.) Royen Fruit Peel: A Phytochemical and Pharmacological Review Karle Pravin P, Dhawale Shashikant C SRP. 2019; 10(1): 11-14 » doi: 0.5530/srp.2019.1.2

- Pharmacognostic and Phytopharmacological Overview on Bombax ceiba Pankaj Haribhau Chaudhary, Mukund Ganeshrao Tawar SRP. 2019; 10(1): 20-25 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1.4

- A Review of Pharmacoeconomics: the key to “Healthcare for All” Hasamnis AA, Patil SS, Shaik Imam, Narendiran K SRP. 2019; 10(1): s40-s42 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1s.21

- A Prospective Review on Phyto-Pharmacological Aspects of Andrographis paniculata Govindraj Akilandeswari, Arumugam Vijaya Anand, Palanisamy Sampathkumar, Puthamohan Vinayaga Moorthi, Basavaraju Preethi SRP. 2019; 10(1): 15-19 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1.3