Research Article - (2024) Volume 15, Issue 9

Abstract

The peels of Musa paradisiaca fruits were investigated for their nutritional and phytochemical compositions, as well as their antioxidant and anti-hyperglycemic activities. Proximate analysis of their composition showed that the major constituents included moisture, carbohydrate, ash, crude fiber and crude fat, with a modest crude protein content. Photochemical present in the aqueous extract of the peels were identified as alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, reducing sugars and amino acids. Additionally, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (HPLC/MS) analysis of the aqueous extract showed the presence of 15 compounds, including phenolic compounds, sterols and sitoindosides. Notably, quercetin constituting about half of these identified compounds. The 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity of the unripe peel extract was significantly higher than that of the ripe peels, with IC50=0.208 mg/L and IC50=0.301 mg/mL, respectively. However, the unripe peels, which demonstrated activity comparable to that of the standard, gallic acid. The α-amylase inhibitory activity of the aqueous extracts of the peels was high. The unripe peels had a higher value IC50=0.024 mg/L, same as acarbose compared to the ripe peels IC50=0.088 mg/mL. The hydroethanolic extract of the unripe peels demonstrated a significantly lower α-amylase inhibitory activity IC50=0.040 mg/mL compared to acarbose IC50=0.024 mg/mL. However, it exhibited a far higher α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, with IC50=0.007 mg/mL and IC50=0.021 mg/mL, respectively. These results support the utilization of Musa paradisiaca peels in human and animal nutrition, with a high potential for applying both aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts of unripe fruit peels in the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes.

Keywords

Musa paradisiaca fruit peels, Proximate composition, Phytochemical classes, composition, Antioxidant activity, α-Amylase inhibitory activity

Introduction

The plant Musa paradisiaca, which bears plantains, belongs to the family Musaceae and the order plantaginaceae. This crop is primarily grown and consumed mostly in the tropical regions of Africa, South America, central America and Asia. It serves as a staple food in Sub-Saharan Africa, especially in Nigeria, where over 2.11 million metric tons of the fruit are produced annually. Plantain provides over 10% of daily calorie intake for a population exceeding 70 million people across the African continent. In Nigeria, various foods made from plantain fruit include roasted plantain, boiled plantain and amala, which is prepared by cooking and stirring flour derived from dried matured unripe fruits in hot water (Adamu AS, et al., 2017). Amala is usually consumed with a variety of Nigerian soups. Other dishes include Emienki, made from flour milled from dried ripe but not overripe fruits, and dodo, which consists offried slices of the ripe fruit. Additionally, kpekererefers tothin-sliced fried slightly ripe or unripe fruit. The preparation of these dishes often involves cooking slurry of flour containing various ingredients, which is then wrapped in broad leaves of ewe eéran (Taumatococcus danielli). The wide range of food applications generates a huge quantity of peels, which account for about 40% of the total fruit weight.

Musa paradisiaca peels show promise as a raw material for industrial use, especially in agro-based industries. In the food industry, flour made from the peels has been reportedly used to enrich wheat flour at various percentages for producing snacks, such as cookies and sausages (Rosero-Chasoy G and Serna-Cock L, 2017). This flour serves as a good source of fiber and antioxidants offering potential benefits for humans in the management and prevention of lifestyle-related chronic diseases (Arun KB, et al.,2018).

The peels of Musa paradisiaca have been considered for various applications beyond the food industry. They are recognized for their potential use as organic fertilizer and as an ingredient in livestock feed (Okareh OT, et al., 2015; Omale J and Okafor PN, 2018).

In the chemical industry, the peels show potential for the production of bioethanol and ash (alkali) for soap manufacture. Additionally, their ethanol extract can be utilized in the preparation of polyphenolic resins for the adsorption of heavy metals due to their high affinity for lead, nickel and chromium (Cordero AF, et al., 2015).

Musa paradisiaca peels have demonstrated variousmedicinal uses, serving as antibacterial and antifungal agents (Auta SA and Kumurya AS, 2015). They also exhibit antiulcer, antidiabetic, analgesic, wound-healing, hair growth promoting and haemostatic activities, among others (Barroso WA, et al., 2019; D’Eliseo D, et al., 2019). In urban areas of Nigeria, the peels of Musa paradisiaca are mostly regarded as waste. If not properly disposed off they can contribute to environmental damage by blocking drains, which can subsequently cause flooding and erosion.

However, the study of the nutritional and phytochemical compositions, as well as the antioxidant, α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of both ripe and unripe peels, could provide valuable insights into their nutritional benefits and therapeutic potentials in managing several diseases, particularly type 2 diabetes mellitus. This study aims to determine the nutritional and phytochemical compositions, as well as the antioxidant and α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of the aqueous extracts of both ripe and unripe peels of Musa paradisiaca fruits, as a guide to their potential use as food and medicine.

Materials and Methods

Musa paradisiaca peels

Matured and healthy ripe and unripe plantains were obtained from Okha market on Sapele road, Benin city, Edo state, Nigeria. The peels were removed and dried to a constant weight in a ventilated oven at 40°C. Later drying, the peels were ground into a power and stored in airtight containers to prevent moisture absorption. The powdered peels were stored in the refrigerator until they were required for analysis.

Reagents

Gallic acid, DPPH, α-glucosidase, α-amylase, and p-nitrophenyl α-glucose D-glucopyranoside were obtained from sigma-aldrich co. st. louis, mo, usa. Citric acid, potato starch, Di-Nitro Salicylic Acid (DNSA), methanol, potassium ferricyanide, ascorbic acid, trichloroacetic acid, Dinitro Phenyl Hydrazine solution (DNPH), thiourea, sodium hydroxide, monosodium dihydrogen phosphate, disodium phosphate, phosphoric acid, nitric acid, absolute ethanol and phenolphthalein were obtained from various sources. All reagents were analytical grade, except for benedict’s reagent and barfoed’s solution, which were reagent grade.

Powdered plantain peel extraction

The extraction process involved using 200 g each of ripe and unripe plantain peels. These were extracted by boiling in 1 L of water or of a hydroethanol solvent H2O/EtOH, 70/30 v/v for 20 minutes. After boiling, the mixture was filtrate red to obtain the liquid extracts. The final filtrates were concentrated using a rotary evaporator at 50°C to obtain the crude aqueous extracts of the peel. These extracts were then preserved in airtight bottles and stored in a refrigerator until they are required for analysis.

Proximate analysis of Musa paradisiaca peels

Determination of moisture, crude fat, crude fiber, ash and crude protein contents was performed according to official methods (AOAC, 2010). Additionally, the carbohydrate content was calculated as Nitrogen Free Extract (NFE).

Qualitative analysis of phytochemicals of plantain peels

The qualitative analysis involved screening the aqueous extract of the peels for various phytochemicals. This included testing for the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, reducing sugars, amino acid or protein and carbohydrate (Barroso WA, et al., 2019)

Quantitative analysis of the composition of the compounds in the aqueous extract of Musa paradisiaca peels

The composition of plantain peel compounds was determined using a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) coupled with a mass spectrometer, outlined by (Cheng LC, et al., 2017).

Antioxidant capacity

The antioxidant capacity was evaluated through two primary methods like DPPH radical scavenging activity and ferric reducing antioxidant power.

DPPH radical scavenging activity: DPPH radical scavenging activity was determined according to the method described by (Tang SZ, et al., 2002).

Ferric reducing antioxidant power: The reducing power was determined according to the method.

Anti-hyperglycaemic activity: This activity was determined by measuring the α-amylase and α-glycosidase inhibitory activates of both the aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts of plantain peels.

Alpha-amylase inhibitory activity: The α-amylase inhibitory activity of the aqueous hydroethanolic extracts of the plantain peels was determined following the methodology and outlined by (Kamtekar S, et al.,2014).

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity: α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was determined according to the method described by (Telagari M and Hullatti K, 2015).

Statistical analysis

All measurements were performed in triplicate and results expressed mean ± Standard Deviation (SD). One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) at a confidence interval of 95% p<0.05 was performed and calculation of IC50 values were carried out using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) statistical software.

Results and Discussion

Proximate analysis of the peels

The results of the proximate analyses of the Musa paradisiaca ripe and unripe peels are presented in Table 1. The ripe plantain peels had a moisture content of 23.17 ± 0.03%, a crude fiber content of 8.63 ± 0.01% Dry Matter (DM), a crude fat content of 12.11 ± 0.01% DM, an ash content of 13.54 ± 0.01% DM, a carbohydrate content of 38.15 ± 0.02% DM and a crude protein content of 4.40 ± 0.06% DM. For the unripe peels, moisture content was 16.31 ± 0.01%, crude fiber content, 12.63 ± 0.1% DM, crude fat content, 13.10 ± 0.02% DM, ash content, 12.01 ± 0.005% DM, carbohydrate content, 39.80 ± 0.4% DM and crude protein content, 6.15 ± 0.14% DM.

| Nutrient g/100 g | Ripe peels | Unripe peels |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 23.17 ± 0.03 | 16.31 ± 0.01 |

| As % Dry matter | As % Dry matter | |

| Crude Fibre | 8.63 ± 0.01 | 12.63 ± 0.10 |

| Crude Fat | 12.11 ± 0.01 | 13.10 ± 0.02 |

| Ash | 13.54 ± 0.01 | 12.01 ± 0.01 |

| Carbohydrate | 38.15 ± 0.02 | 39.80 ± 0.40 |

| Crude Protein | 4.40 ± 0.06 | 6.15 ± 0.14 |

| Gross energy, kcal | 279.19 | 301.7 |

Note: aValues are expressed as Mean ± SD (n=3)

Table 1: Proximate composition of Musa paradisiaca fruit peelsa

Qualitative analysis of phytochemicals in the aqueous extract of Musa paradisiaca peels

The results of the qualitative analysis of the phytochemicals present in the aqueous extract of ripe and unripe Musa paradisiaca peels (Table 2). Identified photochemical were alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, reducing sugars and amino acids (Table 3).

| Phytochemicalsa | Ripe peels | Unripe peels |

|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | + | + |

| Flavonoids | + | + |

| Phenol | + | + |

| Reducing sugar | + | + |

| Amino acid | + | + |

Note: a+= Present

Table 2: Phytochemicals of aqueous extract of ripe and unripe Musa paradisiaca fruit peels.

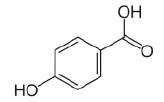

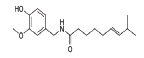

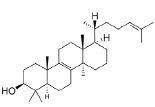

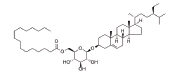

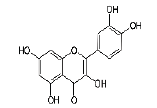

| S/N | Compound | Chemical Structure | Chemical formula | Molecular weight (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | p-Hydroxybenzoic acid |  |

C7H6O3 | 138.122 |

| 2 | Caffeic acid |  |

C9H8O4 | 180.16 |

| 3 | Capsaicin |  |

C18H27NO3 | 305.40 |

| 4 | Lanosterol |  |

C30H50O | 432.8 |

| 5 | Syringin |  |

C17H24O9 | 373.37 |

| 6 | β-Sitosterol |  |

C29H50O | 414.71 |

| 7 | Sitoindoside I |  |

C51H90O7 | 815.26 |

| 8 | Sitoindoside II |  |

C53H92O7 | 841.29 |

| 9 | Myricetin |  |

C15H10O8 | 318.24 |

| 10 | Quercetin |  |

C15H10O7 | 302.236 |

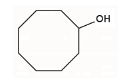

| 11 | Cyclomusatenol* |  |

C8H9O1 | 16.05 |

| 12 | Cyclomusatenone* |  |

C6H10 | 154.25 |

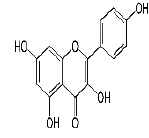

| 13 | Kaempferol |  |

C15H10O6 | 286.23 |

| 14 | Luteolin |  |

C15H10O6 | 286.24 |

| 15 | Apigenin |  |

C15H10O5 | 270.0528 |

Note: *May be artifacts arising during analysis.

Table 3: Chemical structures, chemical formulas, and molecular weights of M. paradisiaca compounds as detected by mass spectrometry.

Quantitative analysis of phytochemicals in the aqueous extract of Musa paradisiaca peels

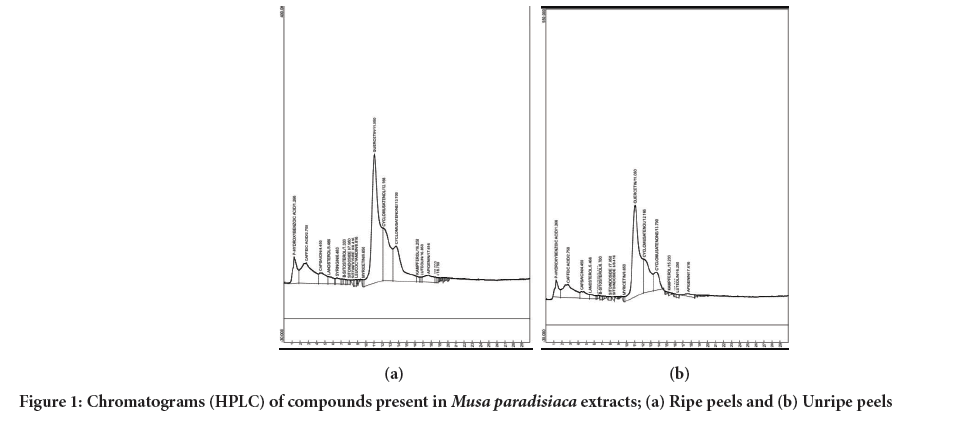

HPLC quantitative analyses of the phytochemical compounds in aqueous extracts of Musa paradisiaca ripe peel indicated the presence of 15 compounds, including phenolic compounds, sterols and sitoindosides (Figure 1, Table 4), with quercetin constituting 49.13% in the unripe peels and 41.75% in the ripe peels followed by caffeic acid at 11.78% for the unripe and 11.29% for the ripe, hydroxybenzoic acid at 4.91% and 5.01% capsaicin at 3.52% and 3.54%, and lanosterol at 1.54% and 1.65%. Additionally, cyclomusatenol was found to be 16.08% in the unripe peels and 15.78% in the ripe peels, while cyclomusatenone was present at 7.91% and 14.53%, respectively. However, the structures assigned did not align with their assigned molecular as and weights, suggesting they may be artifacts arising during the analysis of the extracts. The remaining were minor constituents, each constituting <1% of the total phytochemical content.

Figure 1: Chromatograms (HPLC) of compounds present in Musa paradisiaca extracts; (a) Ripe peels and (b) Unripe peels.

| Composition, g/100 g | ||

|---|---|---|

| Constituents | Ripe | Unripe |

| p-Hydroxybenzoic Acid | 5.01 | 4.91 |

| Caffeic Acid | 11.29 | 11.78 |

| Capsaicin | 3.54 | 3.52 |

| Lanosterol | 1.65 | 1.54 |

| Syringin | 1.17 | 0.34 |

| β-Sitosterol | 0.41 | 0.53 |

| Sitoindoside I | 0.41 | 0.51 |

| Sitoindoside II | 0.35 | 0.44 |

| Myricetin | 0.36 | 0.45 |

| Quercetin | 41.75 | 49.13 |

| Kaempferol | 0.59 | 0.51 |

| Luteolin | 0.28 | 0.48 |

| Apigenin | 2.86 | 1.87 |

Table 4: Composition of compounds in the aqueous extract ofripe and unripe Musa paradisiaca peels.

Antioxidant capacity

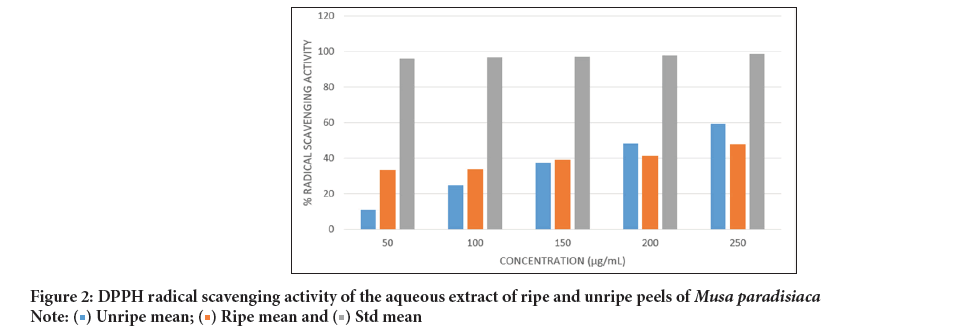

DPPH radical scavenging activity: The DPPH radical scavenging activity of the aqueous extracts of Musa paradisiaca peels are presented in Figure 2. The activity was high and increased with higher concentration. At a concentration range of 0.05-0.25 mg/mL, the extracts of the ripe and the unripe peels exhibited IC50 value of 0.307 mg/mL and 0.208 mg/mL, respectively. Both values were significantly higher than that of the standard, gallic acid which had an IC50 value of 0.161 mg/mL.

Figure 2: DPPH radical scavenging activity of the aqueous extract of ripe and unripe peels of Musa paradisiaca.

.

.

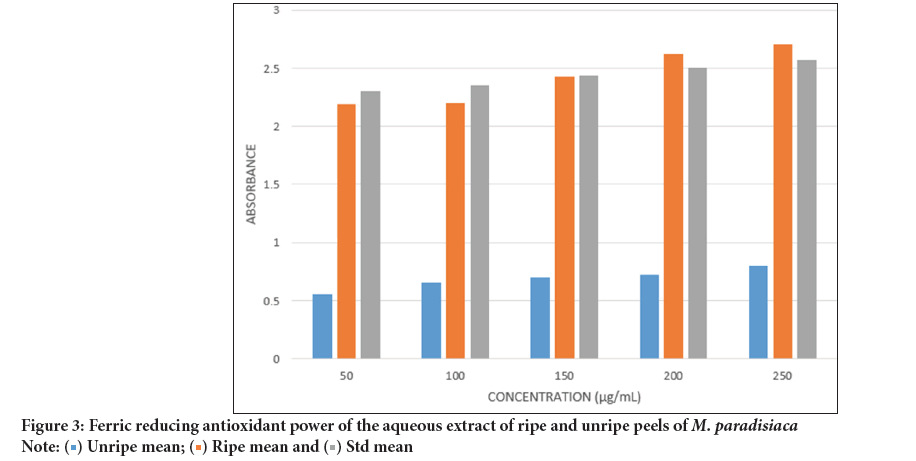

Ferric reducing antioxidant power: The ferric reducing antioxidant power of the aqueous extract of both ripe and unripe Musa paradisiaca peels is shown in Figure 3. At a concentration range of 50-250 µg/mL, the ripe peel extract exhibited a significantly higher activity than that of the unripe peels. Notably, the activity of the ripe peel extract exhibiting activity similar to that of the standard, gallic acid and exceeded it at higher concentrations.

Figure 3: Ferric reducing antioxidant power of the aqueous extract of ripe and unripe peels of M. paradisiaca.

.

.

In contrast, the activity of the aqueous extract from the unripe peels was high with an IC50 value of 0.024 mg/mL, which was much lower than that of the ripe peels, which had an IC50 value of 0.088 mg/mL across all concentrations considered.

Alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the hydroethanolic extract Musa paradisiaca unripe peels: The hydroethanolic extract of Musa paradisiaca unripe peels was examined for its α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities.

The results for these activities, along with those for acarbose, an α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitor drug used for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus, are presented in (Tables 5-6).

| Concentration (mg/mL) | Percentage inhibition (Mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroethanolic* extract of unripe peels of Musa paradisiaca | Acarbose | |

| 0.1 | 70.30 ± 0.55a | 80.66 ± 0.62b |

| 0.2 | 74.73 ± 0.57a | 82.56 ± 0.55b |

| 0.3 | 75.78 ± 0.21a | 84.90 ± 0.44b |

| 0.4 | 77.27 ± 0.32a | 88.76 ± 0.54b |

| 0.5 | 78.49 ± 0.31a | 90.96 ± 0.86b |

| IC50 | 0.040 | 0.024 |

Note: Results are expressed in Mean ± SD (n=3), *Hydroethanol: H2O/EtOH 70:30 v/v, abMeans with different superscripts on the same row differ significantly (p<0.05)

Table 5: Alpha-amylase inhibitory activity of the hydroethanolic extract of the unripe peels of M. paradisiaca and the standard, acarbose.

| Concentration (mg/mL) | Percentage inhibition (Mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroethanolic* extract of unripe peels of Musa paradisiaca | Acarbose | |

| 0.1 | 71.66 ± 0.36a | 74.56 ± 0.15b |

| 0.2 | 73.99 ± 0.43a | 75.54 ± 0.34b |

| 0.3 | 75.41 ± 0.49a | 76.57 ± 0.16b |

| 0.4 | 82.05 ± 0.31a | 78.25 ± 0.56b |

| 0.5 | 82.43 ± 0.26a | 83.08 ± 0.28a |

| IC50 | 0.007 | 0.021 |

Note: Results are expressed in Mean ± SD (n=3), *Hydroethanol: H2O/EtOH 70:30 v/v, abMeans with different superscripts on the same row differ significantly (p<0.05)

Table 6: Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activities of the hydroethanolic extract of the unripe peels of M. paradisiaca and the standard, acarbose.

Table 5 shows the ɑ-amylase inhibitory activity at various concentrations of the hydroethanolic extract of unripe Musa paradisiaca peels compared to acarbose. The percentage inhibition by acarbose was significantly higher at all concentrations studied, with a higher overall activity than the Musa paradisiaca peel extract, with IC50 values of 024 mg/ml vs. 0.040 mg/mL, respectively.

The ɑ-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the hydroethanolic extract of Musa paradisiaca unripe peels and acarbose is shown in Table 6. At concentrations ranging from 0.1-0.4 mg/mL concentrations, the percentage inhibitory activity of the unripe peels 71.66%-82.05% was significantly higher than that of acarbose 74.56%-78.25%, However, there was no significant difference between their activities at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml, 82.43% vs. 83.08%, for acarbose. Overall, the unripe Musa paradisiaca peel extract displayed a considerably higher ɑ-glucosidase inhibitory activity with IC50 value of 0.007 mg/mL, compared to acarbose, which had an IC50 value of 0.021mg/mL.

Proximate composition of the peels

The proximate composition of both the ripe and unripe Musa paradisiaca peels were similar indicating their suitability for use in human and animal nutrition, as ingredient in animal feed, and as an adjunct in flours and meals for human consumption (D’Eliseo D, et al., 2019). For the unripe and semi-ripe fruits used for flour production, whole fruits could be rinsed, sliced without peeling, and dried, prior to grinding into flour. This flour can be blended as required for adequate functionality, with conventional flours produced without the peel.

The results of this study, were similar to those previously reported by (Ighodaro OM, 2012; Shadrach I, et al., 2020), who noted a similar nutritional composition in both the ripe and unripe peels. Additionally, the high ash mineral content observed is consistent with the use of this material as an alkali for soap boiling.

Qualitative and quantitative analyses of the compounds present in the aqueous extract of Musa paradisiaca peels

The results of the qualitative analysis (Table 2) showed the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, reducing sugars and amino acids.

Further, analysis using HPLC-MS revealed a total of 15 compounds, which included phenolic compounds sterols, and sitoindosides (Figure 1). Notably, quercetin consisted almost half of the total compounds identified with levels of 49.13% in the unripe peels and 41.75% in the ripe peels.

Bioactivity of Musa paradisiaca peel aqueous extract compounds

The composition of Musa paradisiaca compounds is shown in Table 4. Quercetin, the dominant constituent, protects insulin secreting pancreatic cells from glucotoxicity. Additionally, quercetin, myricetin and apigenin inhibit Glucose Transporter 2 (GLUT 2), while these compounds along with luteolin, inhibit ɑ-amylase and ɑ-glucosidase activity. Both quercetin and capsaicin exert anti-inflammatory effects by directly blocking Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathways, NFKB activity and the expression of inflammatory cytokines (Hanhineva K et al., 2010; Kumar N and Goel N, 2019; Pico J and Martínez MM, 2019; Anhê FF, et al., 2013).

Furthermore, the phenolic acids p-hydroxybenzoic and caffeic acid are effective free radical scavengers that alleviate oxidative stress markers. They also exhibit antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, ɑ-amylase and ɑ-glucosidase inhibitory activities, as well as neuroprotective and hepatoprotective effects (Hanhineva K et al., 2010; Kumar N and Goel N, 2019).

Sitoindoside I is a potential anticancer agent exhibiting antiproliferative activity against human HT-29 cells, as assessed by a reduction in cell viability after 3 days using the SRB assay (Fraga CG, et al., 2019; Sivakumar B, et al., 2020). Both Sitoindoside I and sitoindoside II, exhibit antiulcerogenic activity (Ghosal S and Saini KS, 1984).

β-Sitosterol promotes antitumorigenic processes in prostate cancer cells and rodent models of prostate cancer. It also exhibits 5α-reductase inhibitory activity similar to that of finasteride and dutasteride, which are widely used to treat prostatic enlargement or Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) (Macoska, J.A, 2023).

Furthermore, it inhibits the binding of the active form of testosterone, Dihydrotestosterone (DHT), to the androgen receptor.

Lanosterol is a key component in maintaining eye lens clarity and a potential agent for the reversal and prevention of cataracts (Huff MW and Telford DE, 2005).

Additionally, kaempferol exhibits anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. It is a potent promoter of apoptosis and regulates a range of signaling pathways within cells. It is relatively less toxic to normal cells than the standard cancer chemotherapy and inhibits the proliferation of cancerous cells by disrupting the cell cycle at checkpoints (Dormán G et al., 2021). One such compound is syringing, a phenolic glycoside which possesses various biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, anti-irradiation, anti-osteoporosis and anticancer activities (Li F et al., 2017; Liu J et al., 2018).

The rising burden of type 2 diabetes is of immense concern in healthcare worldwide. In 2017, approximately 462 million individuals were afflicted by the disease, corresponding to 6.28% of the world’s population. Over 1 million deaths annually, making it the 9th leading cause of mortality. The global prevalence of type 2 diabetes is projected to increase to 7079 individuals per 100,000 by 2030 (Abdul Basith KM, et al.,2020).

At present, in addition to pharmacological interventions, such as oral antidiabetics and insulin, there are less expensive plant-based products. Some existing diabetes treatments such as acarbose work by inhibiting α-amylase and α-glucosidase in the digestive tract, thereby slows starch digestion, and the release and subsequent uptake of glucose, resulting in decreased postprandial glucose levels (Salehi B, et al., 2019).

Thus, Musa paradisiaca peels contain a broad spectrum of bioactive compounds, potentially useful as anti-inflammatory, α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitors, 5α-reductase inhibitors for anti-prostate enlargement, antioxidants, antimicrobial agents and anticancer (antitumorigenic) agents in various therapeutic preparations.

Antioxidant capacity

The antioxidant capacity of the aqueous extract of the Musa paradisiaca peels was determined through its DPPH radical scavenging activity and ferric reducing antioxidant activity. The peels exhibited modest DPPH radical scavenging activity (Figure 2), with the aqueous extract of the unripe peels having higher scavenging activity than the ripe peels however, both exhibited lower activity compared to gallic acid of the same concentration.

Ferric iron reducing activity, the aqueous extract of the ripe peels showed high values, similar to those of the standard, gallic acid across all concentrations considered. In contrast, the ferric reducing activity for the extract of Musa paradisiaca peelsbut was much lower (Figure 3).

Overall, the aqueous extract of Musa paradisiaca peels may be useful in the prevention and management of this oxidative stress related conditions (Oduje AA, et al.,2015).

Anti-hyperglycaemic activity

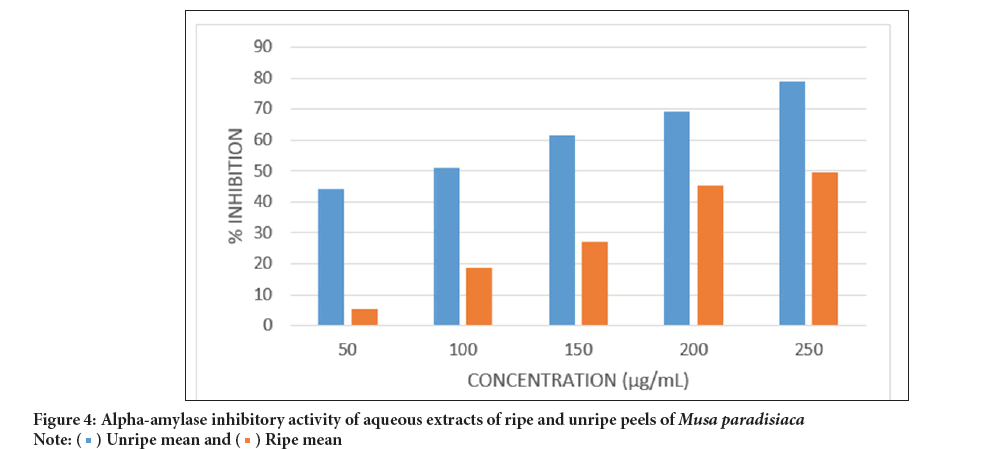

Alpha-amylase inhibitory activity of the aqueous extract of Musa paradisiaca unripe peels: The anti-hyperglycaemic activity of the aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts of the Musa paradisiaca peels was determined by assessing their α-amylase and α-glycosidase inhibitory activities, compared them with those of acarbose, a drug used for the management of type 2 diabetes in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Alpha-amylase inhibitory activity of aqueous extracts of ripe and unripe peels of Musa paradisiaca.

.

.

The extracts exhibited significant α-amylase inhibitory activity, consistent with their high content of compounds know to inhibit these enzymes. The activity of the aqueous extract of the unripe peels was high, surpassing that of the ripe peels IC50, value of 0.024 mg/mL for unripe vs. 0.088 mg/mL for ripeacross all concentrations considered. This difference aligns with the higher concentration of enzyme inhibitors found in the unripe peel extract (Table 4). However, the IC50 values for the unripe extract and acarbose were comparable 0.24 mg/mL (Table 5) (Evans WC, 1997).

Alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the hydroethanolic extract Musa paradisiaca unripe peels

Results for the hydroethanolic extracts of the Musa paradisiaca unripe peels and acarbose, (Table 5) show that α-amylase inhibitory activity of the hydroethanolic extract was high, and similar to that of acarbose; however, it was significantly lower IC50, values of 0.040 mg/mL vs. 0.024 mg/mL for acarbose. Conversely, the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of this extract was much higher than that of acarbose IC50=0.007 mg/mL for the extract vs. 0.021 mg/mL for acarbose.

Conclusion

Musa paradisiaca fruit peels are rich sources of macronutrients, dietary fiber and minerals, making them suitable for utilization in both human and animal nutrition. They contain a broad spectrum of bioactive compounds, potentially useful as anti-inflammatory, α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory, 5α-reductase inhibitors for anti-prostate enlargement, antioxidants, antimicrobial agents, and anticancer antitumorigenic agents in various therapeutic preparations. Their aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts exhibited high in vitro antioxidant capacity as well as α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities comparable to those of acarbose, with high potential for use in the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

References

- Adamu AS, Ojo IO, Oyetunde JG. Evaluation of nutritional values in ripe, unripe, boiled and roasted plantain Musa paradisiaca pulp and peel. Eu J Basic Appl Sci. 2017; 4(1): 2059-3058.

- Rosero-Chasoy G, Serna-Cock L. Effect of plantain Musa paradisiaca dominico harton peel flour as binder in frankfurter-type sausage. Acta Agron. 2017; 66(3): 305-310.

- Arun KB, Madhavan A, Reshmitha TR, Thomas S, Nisha P. Musa paradisiaca inflorescence induces human colon cancer cell death by modulating cascades of transcriptional events. Food Funct. 2018; 9(1): 511-524.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Okareh OT, Adeolu AT, Adepoju OT. Proximate and mineral composition of plantain Musa Paradisiaca wastes flour; a potential nutrients source in the formulation of animal feeds. Afr J Food Sci Technol. 2015; 6(2): 53-57.

- Omale J, Okafor PN. Comparative antioxidant capacity, membrane stabilization, polyphenol composition and cytotoxicity of the leaf and stem of Cissus multistriata. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008; 7(17).

- Cordero AF, Gómez M, Castillo JH. Polyphenolic resin synthesis: Optimizing plantain peel biomass as heavy metal adsorbent. Polímeros. 2015; 25(4): 351-355.

- Auta SA, Kumurya AS. Comparative proximate, mineral elements and antinutrients composition between Musa sapientum (Banana) and Musa paradisiaca (Plantain) pulp flour. Sky J Biochem Res. 2015; 4(4): 025-030.

- Barroso WA, Abreu IC, Ribeiro LS, da Rocha CQ, de Souza HP, de Lima TM. Chemical composition and cytotoxic screening of Musa cavendish green peels extract: Anti proliferative activity by activation of different cellular death types. Toxicol In Vitro. 2019; 59: 179-186.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- D’Eliseo D, Pannucci E, Bernini R, Campo M, Romani A, Santi L, et al. In vitro studies on anti-inflammatory activities of kiwifruit peel extract in human THP-1 monocytes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019; 233: 41-46.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) official methods of analysis. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 2010.

- Cheng LC, Murugaiyah V, Chan KL. Developing a validated HPLC method for the phytochemical analysis of antihyperuricemic phenylethanoid glycosides and flavonoids in Lippia nodiflora. Nat Prod Commun. 2017; 12(11): 1934578X1701201105.

- Tang SZ, Kerry JP, Sheehan D, Buckley DJ. Antioxidative mechanisms of tea catechins in chicken meat systems. Food Chem. 2002; 76(1): 45-51.

- Kamtekar S, Keer V, Patil V. Estimation of phenolic content, flavonoid content, antioxidant and alpha amylase inhibitory activity of marketed polyherbal formulation. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2014; 4(9): 061-065.

- Telagari M, Hullatti K. In-vitro α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of Adiantum caudatum linn. and celosia argentea linn extracts and fractions. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015; 47(4): 425-429.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ighodaro OM. Evaluation study on nigerian species of Musa paradisiaca peels. Researcher. 2012; 4(8): 17-20.

- Shadrach I, Banji A, Adebayo O. Nutraceutical potential of ripe and unripe plantain peels: A comparative study. Chem Int. 2020; 6(2): 83-90.

- Hanhineva K, Törrönen R, Bondia-Pons I, Pekkinen J, Kolehmainen M, Mykkänen H, et al. Impact of dietary polyphenols on carbohydrate metabolism. Int J mol Sci. 2010; 11(4): 1365-1402.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumar N, Goel N. Phenolic acids: Natural versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnol Rep. 2019; 24: e00370.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pico J, Martínez MM. Unraveling the inhibition of intestinal glucose transport by dietary phenolics: A review. Curr Pharm Des. 2019; 25(32): 3418-3433.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anhê FF, Desjardins Y, Pilon G, Dudonné S, Genovese MI, Lajolo FM, et al. Polyphenols and type 2 diabetes: A prospective review. Pharm Nutr. 2013; 1(4): 105-114.

- Fraga CG, Croft KD, Kennedy DO, Tomás-Barberán FA. The effects of polyphenols and other bioactives on human health. Food Funct. 2019; 10(2): 514-528.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Sivakumar B, Boovarahan SR, Kurian GA. Anti-proliferative potential of sodium thiosulfate against HT 29 human colon cancer cells with augmented effect in the presence of mitochondrial electron transport chain inhibitors. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2020; 10(7): 333-340.

- Ghosal S, Saini KS. Sitoindosides I and II, two new anti-ulcerogenic sterylacyl glucodises from Musa paradisiaca. J Chem Res. 1984; (4).

- Macoska J.A. The use of beta-sitosterol for the treatment of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia.Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2023; 11(6): 467-480.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huff MW, Telford DE. Lord of the rings-the mechanism for oxidosqualene: Lanosterol cyclase becomes crystal clear. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005; 26(7): 335-340.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dormán G, Flachner B, Hajdú I, András C. Target identification and polypharmacology of nutraceuticals. J Nutraceuticals. 2021. 315-343.

- Li F, Zhang N, Wu Q, Yuan Y, Yang Z, Zhou M, et al. Syringin prevents cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure overload through the attenuation of autophagy. Int J Mol Med. 2017; 39(1): 199-207.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu J, Zhang Z, Guo Q, Dong Y, Zhao Q, Ma X. Syringin prevents bone loss in ovariectomized mice via TRAF6 mediated inhibition of NF-κB and stimulation of PI3K/AKT. Phytomedicine. 2018; 42: 43-50.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdul Basith KM, Hashim MJ, King JK, Govender RD, Mustafa H, Al Kaabi J. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes-global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020; 10(1): 107-111.

- Salehi B, Ata A, Anil Kumar N, Sharopov F, Ramírez-Alarcón K, Ruiz-Ortega A, et al. Antidiabetic potential of medicinal plants and their active components. Biomolecules. 2019; 9(10): 551.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oduje AA, Oboh G, Ayodele AJ, Stephen AA. Assessment of the nutritional, anti-nutritional, and antioxidant capacity of uripe, ripe, and over ripe plantain Musa paradisiacal Peels. Int J Curr Adv Res. 2015; 3: 63-72.

- Evans WC. Trease and Evans' pharmacognosy. Gen Pharmacol. 1997; 2(29): 291.

Author Info

Fred Omon Oboh*, Samuel Edosewele Ugheighele, Destiny Damiete Davidson and Naomi Eseohe UgbevaCitation: Oboh FO: Nutritional, Phytochemical Composition and In Vitro Functional Properties of Ripe and Unripe Plantain (Musa paradisiaca) Fruit Peels

Received: 03-Sep-2024 Accepted: 23-Sep-2024 Published: 30-Sep-2024, DOI: 10.31858/0975-8453.15.9.302-310

Copyright: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ARTICLE TOOLS

- Dental Development between Assisted Reproductive Therapy (Art) and Natural Conceived Children: A Comparative Pilot Study Norzaiti Mohd Kenali, Naimah Hasanah Mohd Fathil, Norbasyirah Bohari, Ahmad Faisal Ismail, Roszaman Ramli SRP. 2020; 11(1): 01-06 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2020.1.01

- Psychometric properties of the World Health Organization Quality of life instrument, short form: Validity in the Vietnamese healthcare context Trung Quang Vo*, Bao Tran Thuy Tran, Ngan Thuy Nguyen, Tram ThiHuyen Nguyen, Thuy Phan Chung Tran SRP. 2020; 11(1): 14-22 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1.3

- A Review of Pharmacoeconomics: the key to “Healthcare for All” Hasamnis AA, Patil SS, Shaik Imam, Narendiran K SRP. 2019; 10(1): s40-s42 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1s.21

- Deuterium Depleted Water as an Adjuvant in Treatment of Cancer Anton Syroeshkin, Olga Levitskaya, Elena Uspenskaya, Tatiana Pleteneva, Daria Romaykina, Daria Ermakova SRP. 2019; 10(1): 112-117 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1.19

- Dental Development between Assisted Reproductive Therapy (Art) and Natural Conceived Children: A Comparative Pilot Study Norzaiti Mohd Kenali, Naimah Hasanah Mohd Fathil, Norbasyirah Bohari, Ahmad Faisal Ismail, Roszaman Ramli SRP. 2020; 11(1): 01-06 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2020.1.01

- Manilkara zapota (L.) Royen Fruit Peel: A Phytochemical and Pharmacological Review Karle Pravin P, Dhawale Shashikant C SRP. 2019; 10(1): 11-14 » doi: 0.5530/srp.2019.1.2

- Pharmacognostic and Phytopharmacological Overview on Bombax ceiba Pankaj Haribhau Chaudhary, Mukund Ganeshrao Tawar SRP. 2019; 10(1): 20-25 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1.4

- A Review of Pharmacoeconomics: the key to “Healthcare for All” Hasamnis AA, Patil SS, Shaik Imam, Narendiran K SRP. 2019; 10(1): s40-s42 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1s.21

- A Prospective Review on Phyto-Pharmacological Aspects of Andrographis paniculata Govindraj Akilandeswari, Arumugam Vijaya Anand, Palanisamy Sampathkumar, Puthamohan Vinayaga Moorthi, Basavaraju Preethi SRP. 2019; 10(1): 15-19 » doi: 10.5530/srp.2019.1.3